Translate Page

John Breglio on the evolution of New York theatre

---

Could legendary producers of the past hack it on Broadway today?

If anyone could guess, it's John Breglio. In his new book I Wanna Be a Producer: How to Make a Killing on Broadway...or Get Killed, the noted entertainment lawyer and commercial producer gives a show biz tutorial – with plenty of back-stage anecdotes – on the skills a contemporary Broadway producer must have to shepherd a hit.

He chronicles in detail the steps in producing a show, and he also charts the dramatic changes in producing for the commercial theatre over his 40-plus year career. (For more on those changes, read the first part of our conversation.)

So what would noted producers of the past make of the Broadway world in 2016, what with "royalty pools," partnerships with not-for-profit theatres, and the long journey of a new production through readings, workshops, and labs?

Some would fare better than others. "I remember Morty Gottlieb coming to me about a new play in the late 80s," Breglio says, referring to the Tony Award-winning producer of hits like Sleuth and The Killing of Sister George. "He was used to doing plays for $350,000, and he couldn't get his arms around [the concept] of royalty pools. 'Aw, I don't understand any of it,' he'd say, and he was one of the great play producers."

And what about David Merrick, whose publicity stunts were as legendary as his knack for creating hits? "With Merrick, it was all about control," Breglio says. "He probably would have embraced it because he was very smart, and the new royalty pool structure favored the producers and investors."

{Image1}

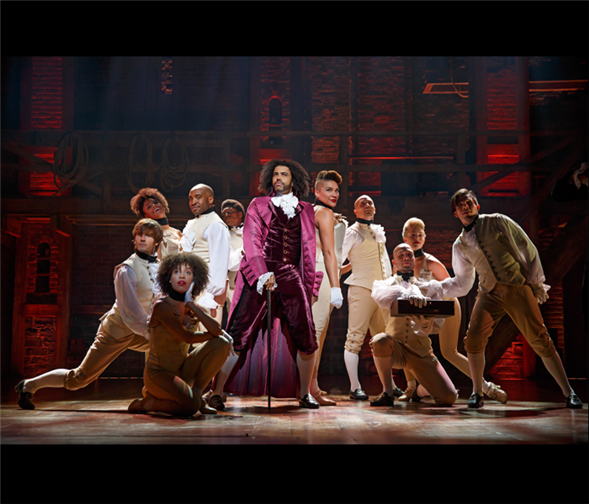

On a separate subject, Breglio says the brouhaha over the Hamilton actors' participation in profits of the show is not a game-changer, despite the news headlines.

Since Michael Bennett voluntarily gave actors who performed in workshops of A Chorus Line a small percentage of future profits, this practice has evolved into the standard sharing structure for developing new shows.

"That agreement permits producers to workshop a show for low salaries, but in return they give the actors a piece of the royalty and subsidiary rights to the show," Breglio says.

But he adds that the structure changed a few years ago when producers went to Actors Equity Association: "They said, 'What if we pay actors twice as much money instead of the royalty agreement?' So now what we have is a 'lab agreement,' and producers have both options. That's what they did in Hamilton, and the actors signed that agreement."

However, after the phenomenal success of Hamilton, Breglio says, "They brought moral persuasion to the table and producer Jeffrey Seller wisely gave them a share as well. He didn't want to lose Tony votes."

Speaking of Bennett, Breglio also uses his book to discuss his professional relationship with the director-choreographer.

Before Bennett died of AIDS in 1987, he was considering several projects, including a stage musical based on the film Easter Parade. "But after watching the movie again and again, Michael felt it was perfect as is and he could not improve on it," Breglio recalls.

That decision still resonates: "Michael taught me so much. When people say, 'I want to do a musical,' based on whatever, I listen and then ask, 'Why?' And nine times out of ten they look at me blankly. Basically what they're saying is the movie or whatever made a fortune, so therefore they will make a fortune by turning it into a musical."

Would the Michael Bennett story be a worthy subject for the stage?

"Surprisingly enough, no one has ever talked about it," Breglio says. "If you read my book you begin to understand how remarkable a man he was and how remarkable that whole period was. It's not a bad idea, but you need a brilliant writer."

He continues, "I don't throw the word around ever, but I worked with four geniuses in the theatre: August Wilson, Stephen Sondheim, Joe Papp, and Michael Bennett. But Michael was so different from all of them. Everything came from the gut. He defined the term 'street smart.' He was 'street brilliant.'"

Want more insight on producing for Broadway? Read Part One of our conversation with John Breglio.

---

Follow Frank Rizzo at @ShowRiz. Follow TDF at @TDFNYC.

Top image: A scene from Hamilton, photographed by Joan Marcus. Photo of John Breglio by Nan Knighton.