Translate Page

How Katsura Sunshine is introducing New York audiences to the timeless comedy of rakugo

---

How did Katsura Sunshine, a white guy from Canada, become a master of rakugo, a traditional Japanese form of storytelling? It's a quirky tale which he recounts with self-deprecating humor along with fables in his "sit-down comedy" solo show Katsura Sunshine's Rakugo, currently at New World Stages.

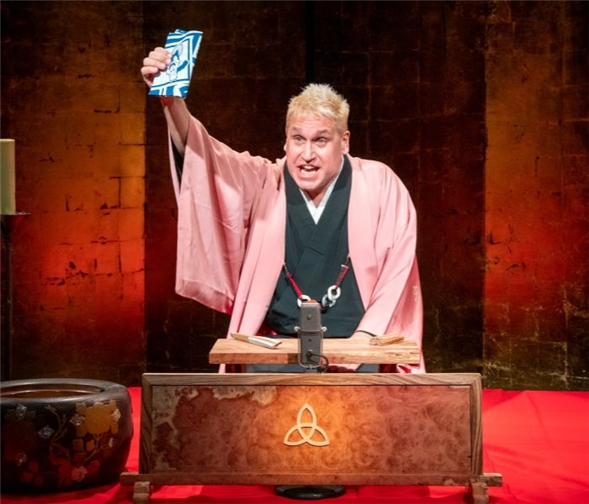

Sunshine, whose birth name is Gregory Robic, first encountered rakugo in 2004, about five years after he'd moved to Japan to study Noh and Kabuki theatre, and he recalls that he was "immediately hooked." Done in restaurants and bars throughout Japan, rakugo follows a strict format. Clad in a kimono, the storyteller sits on a pillow with a fan and hand towel as his sole props. The first part of his performance is similar to a Western stand-up comedy routine, as he introduces himself and attempts to establish a rapport with the audience. The second half, however, is devoted to the centuries-old practice of recounting two or three funny folk tales or fables, in which the storyteller assumes all the roles, modifying his voice and facial expressions to delineate the characters. Each one ends with a punch line.

"My shows in Canada were based on ancient Greek theatre," says Sunshine, 49, who majored in classical theatre in college, and mounted a musical adaptation of Aristophanes' comedy The Clouds that ran for 15 months in his native Toronto before leaving for Japan. "I always liked traditional theatre. Rakugo was comedy, I liked comedy. And I love Japanese traditional stuff. So everything I kind of liked my whole life was in this one art form."

After falling for rakugo, Sunshine spent three years attending countless performances and befriending practitioners. Eventually, he asked Katsura Sanshi, one of the most respected and popular rakugo masters in Osaka, if he could train with him—a big request since Westerners are rarely schooled in the medium.

It took eight months for Sanshi to agree. Once he did, Sunshine signed up for the customary three-year apprenticeship, which he describes as akin to "indentured servitude." He and two other apprentices washed their master's clothes, prepared his meals, and functioned as his stagehands, technical crew and dressers. In exchange, they received free housing, a stipend of a few hundred dollars a month and access to his techniques.

In their spare time, Sunshine and his cohorts learned tales from the rakugo canon, which the master would critique. "It took me a long time to memorize stories in correct Japanese," Sunshine says. Once he deemed Sunshine competent, Sanshi invited him to perform as his warm-up act. Sunshine compares the experience of telling well-known fables about cheating wives and village drunks to that of jazz musicians playing standards: it's the improvisations that distinguish one artist from another.

Sunshine says Sanshi encouraged him to dye his hair blonde to emphasize his foreignness. He also gave Sunshine his stage name.

It's traditional for trainees to take the surname of their masters, Katsura in this case. Sunshine's first name is also derived from his master's moniker. The kanji, or character, for "San" sounds like sun, and Sanshi intentionally chose the kanji for shine as the second syllable, because the word sunshine would resonate in both English and Japanese.

There was no formal graduation ceremony at the end of Sunshine's three-year term. "He just tosses you out into the world and you start working," Sunshine says. But Sanshi's reputation and the exposure Sunshine gained as his opening act made it easy for the novice to land gigs.

Although some of Japan's other 800 recognized rakugo masters may have had reservations about admitting an outsider into their community, Sunshine says Japanese audiences have been welcoming. His foreignness is sometimes even an attraction. "But in the end, you have to be funny," he says. "You have to be entertaining."

His show at New World Stages is performed in English, and though the stories, which change monthly, are rooted in Japanese culture, all are relatable and delightful.

His devotion to the craft has shielded Sunshine from charges of cultural appropriation. In fact, many Japanese expatriates have attended his Off-Broadway production since it began last fall, and their enthusiastic reception has dispelled any sense of impropriety.

"The atmosphere and the setting and the kimono are kind of window dressing," Sunshine says. "The jokes are very much to do with basic human relationships. They're universal."

---

TDF MEMBERS: At press time, discount tickets were available for Katsura Sunshine's Rakugo. Go here to browse our current offers.

Janice C. Simpson writes the blog Broadway & Me and hosts the BroadwayRadio podcast Stagecraft.

Top image: Katsura Sunshine in Rakugo. Photo by Russ Rowland.