Translate Page

Why TV star Gbenga Akinnagbe's Broadway debut feels so personal and important

---

Most wouldn't see a link between stone-cold killer Chris Partlow from HBO's The Wire, flashy pimp-turned-porn-star Larry Brown on HBO's The Deuce and Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman in Broadway's To Kill a Mockingbird. But Gbenga Akinnagbe, the actor who has brought all three to life, notices a strong connection.

"All of these characters are just trying to get through each day the best way they know how," says Akinnagbe, who's making his Broadway debut in Aaron Sorkin's stage adaptation of Harper Lee's beloved Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. "All of them have things they are fighting for and fighting against. Larry is just trying to do what he can for him and his family. Chris is getting by with the skill set and limitations he has. And Tom is the same, facing the challenges of this town and this time period," the fictional Maycomb, Alabama in the 1930s.

Born in the U.S. to Nigerian immigrant parents, Akinnagbe first read To Kill a Mockingbird in eighth grade. "I liked it as an entertainment, but I didn't realize the writer was shining a light on the times," he says. "Ironically enough, I felt like I was living those times, growing up in the projects in Maryland."

According to Akinnagbe, he was placed in special ed beginning in second grade because administrators mistook his impoverished circumstances for impairment. "I was kicked out of school for the first time in kindergarten," he recalls. "They always try to prescribe drugs when all you really need is three regular meals a day, or a parent at home or shoes without holes in them."

His situation changed when he took up wrestling in high school. "In wrestling, you learn the limitations of your body and mind, and learn that most of the time those limitations are made up and you can surpass them," he says. "I've tried to apply that to every aspect of my life." Akinnagbe became a champion in the sport, which helped him win a scholarship to Bucknell University where he majored in English and political science.

After graduating, he worked at a federal agency for a time, then decided he wanted to become actor. He read up on the profession and started going on auditions, landing stage roles in the Washington, D.C. area.

His big break came when he was cast as Chris Partlow, chief enforcer for an illicit drug ring on The Wire. In the years since that acclaimed series ended in 2008, he has appeared on some two dozen TV shows, including memorable stints on The Good Wife, Nurse Jackie and The Following, then landed his starring gig as Larry Brown on The Deuce.

"After The Wire, I was offered a lot of roles as a bad guy who kills people," he says. Akinnagbe turned them all down. "The writing wasn't as good as The Wire and the characters didn't make sense. I am not interested in characters who are created to sell black poverty porn or black pain porn. I like characters who have layers to them. They are part of a larger context to understand systems and communities. I choose roles where I get to play people who are either underrepresented or their views are underrepresented."

Last year, Sorkin invited Akinnagbe to participate in a two-day workshop of his take on To Kill a Mockingbird. "A few days later he e-mailed me and asked if I would like to do it on Broadway," the actor says. "I was shocked."

{Image1}

In a piece the Oscar-winning writer penned for New York Magazine, Sorkin stated that he wanted his play to take a new look at the story, because "things have happened in the past 58 years" and "theatres aren't museums." Some of his changes prompted a lawsuit by the late author's estate; producer Scott Rudin countersued. In recounting the negotiations that led to a settlement last May, Sorkin was clear that he saw the alterations to the narrative's two black characters -- Tom, the man Atticus Finch (Jeff Daniels) defends in court, and Calpurnia (LaTanya Richardson Jackson), the nanny for Atticus' children -- as crucial. Even though Tom's life hangs in the balance, he isn't heard from directly until about halfway through both the 1960 novel and the 1962 movie starring Gregory Peck. Tom's first dialogue comes after a lynch mob is driven from the jail where he is waiting to stand trial. "Mr. Finch? They gone?"

In his play, Sorkin added an earlier scene, with Atticus visiting Tom in jail and asking to represent him.

"Atticus comes in all hopeful that there's something to be done, and Tom tells him, 'I was guilty as soon as I was accused,'" Akinnagbe says. "He's pushing back with the realities of his circumstances. In the book and the movie, he accepts whatever this benevolent white savior would do in order to save him. In the play, he's become an agent of his own defense. Bart [Sher, the director] said just a couple of weeks ago that Tom's choice to fight the charges and trust in Atticus and not take a plea deal is the most important decision in the entire play. Without that decision, the play doesn't happen."

Not everything has been changed to accommodate the sensibilities of a 21st-century audience. Notably, the production frequently employs the N-word. "That word flies around in the play a lot, and I know it's disturbing to a lot of people white and black," Akinnagbe says. "I've never been around so many white people saying the N-word!" But the actor understands its importance for this show. "It becomes a lesson in how derogatory words or thoughts get layered into our perceptions of others. It's how people accept the dehumanization of other people. The use of the N-word is a great example of that."

Despite his busy stage and screen schedule, Akinnagbe, an activist as well as an actor, still manages to run Liberated People, a clothing company he founded seven years ago that helps raise money for nonprofits. Twenty percent of all sales of the line's signature item, the Trayvon hoodie, benefit the Trayvon Martin Foundation.

He also finds time to reread To Kill a Mockingbird. "Every once in a while, I step back into that town and see what's been happening since I've been gone," he says. "That's the way it feels." One of his favorite passages in the book is when Atticus tells his son Jem that real courage is not "a man with a gun in his hand. It's when you know you're licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no matter what."

In the stage adaptation, however, Akinnagbe's fondest of the line that begins and ends the play: "All rise." The phrase indicates that court is in session, but it's also "like a call to action for everybody to rise up to what we can be," he notes.

Akinnagbe, who turned 40 the day before the play opened last December, cherishes his To Kill a Mockingbird role because "in hindsight, it puts my life experience into words -- and it looks pretty similar to a lot of other back people," he says. "So telling the story of Tom Robinson is telling the story of the United States."

---

Jonathan Mandell is a drama critic and journalist based in New York. Visit his blog at NewYorkTheater.me or follow him on Twitter at @NewYorkTheater. Follow TDF at @TDFNYC.

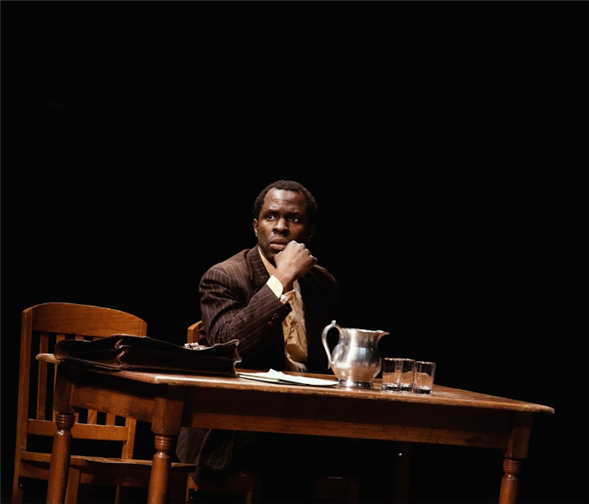

Top image: Gbenga Akinnagbe in To Kill a Mockingbird. Photos by Julieta Cervantes.

TDF MEMBERS: Go here to browse our latest discounts for dance, theatre and concerts.