Manual Cinema wants you to witness how they work

---

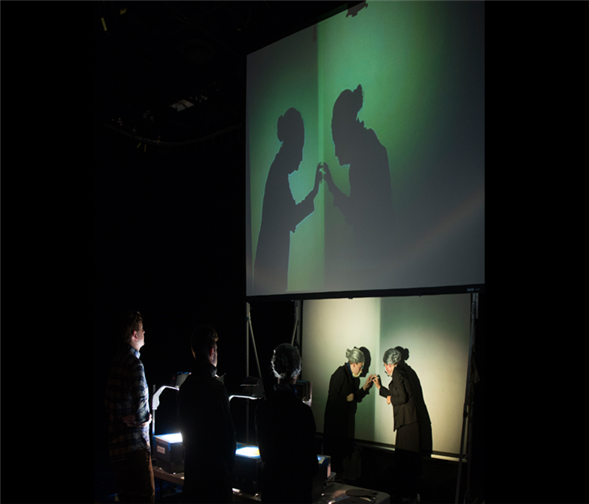

There's a moment on screen, pictured above, when an old woman looks at herself in the mirror. The tentative way she touches the glass communicates her loneliness, her grief, and her disbelief that she's still alive while her beloved sister is in the ground.

That's a highlight of

Ada/Ava, a shadow puppet piece by the Chicago-based troupe Manual Cinema. As it unfolds on a large screen that hangs above our heads at 3-Legged Dog, the story of inseparable twin sisters arguably becomes more powerful because of its simplicity. Ava, the sister who lives, doesn't speak a single word as she adapts to life without Ada, but the way she brews tea or changes the light in a lighthouse or ponders her own reflection makes her feelings explicitly clear. It's a testament to the power of puppets – of silhouettes and paper cut-outs – to embody complex things.

Yet at the same time,

Ada/Ava is a wild ride. That's because we can see

beneath the screen as well, where the cast of performers, puppeteers, sound technicians, and live musicians creates the show. During the mirror scene, for instance, we watch two actresses carefully time their movements to make it seem like Ava's looking at herself. If one performer's hand falls a second behind the other's, then the effect will be destroyed.

This adds a jolt of tension to the entire affair. Even as we're moved by Ava's story, we might be thinking, "How are they going to use that keyboard?" or "Oh no! They dropped a piece of paper! Will that screw them up?"

This complexity is crucial to Manual Cinema's approach.

"We love movies," says Sarah Fornace, a co-artistic director and puppeteer. "We love the cinema. That's a large part of why we do what we do. But so much of seeing movies is about having your focus directly controlled. They want you to look at certain places, and you look there. We're really interested in giving the audience a sense of choice. You could watch us make it; you could watch the musicians; you could watch the top screen. At any moment, you can switch your gaze, and we try to leave space for that."

Julia Miller, another co-artistic director and the actor who plays Ada, adds, "We're telling you this story that's hopefully meaningful, but we're also giving you the spectacle of all the chaos it takes to make the show."

{Image1}

And that chaos matters. "I'm always surprised when people ask us why we don't just make it into a movie," says Fornace. "I'm like, 'Well, because we're making it in real time!' That's such a huge part of the feat we're trying to accomplish, that everything is being made in real time."

Miller adds that since

Ada/Ava was specifically created for the theatre, it wouldn't work as a movie anyway. Or at least, it would work very differently. That mirror scene would lose its tightrope-walking sense of danger if we didn't see the actors executing it.

However, Manual Cinema didn't always put its process on display. In the company's earliest productions, the performers were hidden and audiences only saw the projected puppetry. The troupe realized this was obscuring its intentions as well as its stage business.

As Miller recalls, "We'd invite people up after the show, and they'd say, 'Where's the cam-- what? WHAT?!?!' They really didn't understand that it was being made in front of them, so that was an exciting gift, to provide the audience with more access to the medium."

Conversely, if they can see what's behind the curtain, then patrons can impact the show. "You can feel them more," says Fornace. "We can respond to the audience in little ways. We can push a little bit more into the joke, or if we feel like people need it, we can stretch out one of the dissolves coming out of the funeral scene or something."

She continues, "A lot of the pacing is controlled by how long a shot wants to live and where the music is at any given moment, but it's nice to be able to respond to the audience, which is harder to do when there's a screen between you and them."

---

Mark Blankenship is the editor of TDF Stages.

Photos by Howard Ash. Top photo: The mirror scene in Ada/Ava.