Translate Page

A new play lets female inmates speak for themselves

---

What do incarcerated women want men to understand about their lives? What might happen theatrically if you asked that question then put it aside?

These inquiries led the first and second stages of Key Change, a 60-minute piece of potent, stripped-down storytelling, developed by the UK's Open Clasp theatre company with female inmates of Her Majesty's Prison Low Newton.

Commissioned by Dilly Arts, an organization that specializes in art developed in prisons, the piece was originally intended to be performed for male and female inmates. Artists from Open Clasp – including writer Catrina McHugh, director Laura Lindow, and several actors – worked with incarcerated women to create the show, and some of those prisoners then became performers when the piece toured prison facilities in the UK.

Since then, however, Key Change has extended far beyond those walls. A production at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival – with professional actors replacing the inmates in the cast --- won the Carol Tambor Best of Edinburgh Award. That honor spurred the show's transfer to New York, where it plays through January 31 at the 4th Street Theatre.

Key Change explores the experiences of incarcerated women through stories of physical abuse, drug addiction, and fractured family relationships. This is bare bones theatre – no scenery, masking tape demarcating space, chairs thumped into place where required, few sound and light cues. The spare approach focuses our attention on the unforgettable stories.

McHugh and Lindow recall that some of the incarcerated women who participated in the project wanted men to know what exactly they'd been through, while others were more concerned with demonizing them. "In some respects that very question [of what they wanted men to know] became a problem," says McHugh. "So we put the question to one side, and we just used drama techniques to create discussion, not thinking about the play itself."

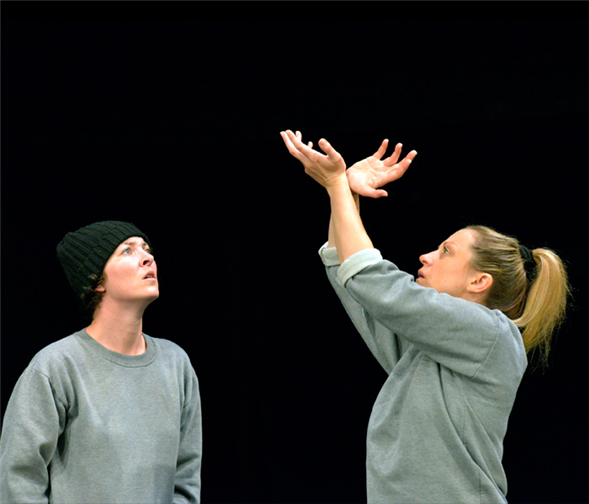

What the women devised and McHugh wrote is a poetic, painful, and often funny interplay among inmates Lucy (Cheryl Dixon), Angie (Jessica Johnson), Kelly (Christina Berriman Dawson), Kim (Judi Earl), and Lorraine (Victoria Copeland). They share stories of early pregnancies, serious drug addictions, and abuse as children or at the hands of sexual partners. They all are survivors who often lead with humor.

{Image1}

Though Open Clasp generally extends their devising process over many months, their limited access to prisoners forced them to compress their timeline. "I think from beginning to end we had four full days, eight sessions, every Friday in the chapel," McHugh recalls. "We stopped for a week, I wrote the script, then went back. Then we had eight more sessions with the women to rehearse them to the point so they could perform." The prisoner devising team, selected by the prison, originally had ten women, though participants came in and out of the project as they moved in and out of prison. Together, this group built the characters of the play, one by one, out of the inmates' lives.

At a talkback after a recent performance, the Key Change actresses reflected on their sense of responsibility to the true stories they were telling. "I know there's a lot of dark subject matter within the play," one said. "I don't want anyone to think that there wasn't that. These were great women. It took a while to build their trust up, but once it was there, they really got into the process and they were passionate about it as well."

Another performer noted, "What's really important for us is that we still feel like the women are with us. This wasn't just a matter of taking stories off people. We worked closely with the women."

Discussing the prison environment itself, a performer said, "The environment is more intimidating than the women. If you think when you go in that you're going to be scared of the women, why would you be? It's the place: it's the razor wire; it's the walls; it's the restrictiveness."

Also at the talkback, Evan Stark, a retired Rutgers professor and creator of the coercive control framework for understanding domestic abuse, reflected on a powerful sequence in the show. A speech outlines types of controlling partners: The Bully and The Headworker and The Jailer and The Sexual Controller and The King of the Castle and The Liar and The Persuader and The Dominator. On stage, the verbally choreographed sequence delivers a thunderous emotional punch. "If you want to understand coercive control," Stark noted, "all you have to do is put all of these characters into a single home and into a single person and subject a single woman and her children to that."

It matters that these social dynamics are explored on stage, where sociological ideas become physical realities. To that end, Open Clasp pursues personal and social transformation through art. McHugh notes they are trying to change the world one play at a time, with the best theatre they can make. "If the theatre's not brilliant," she says. "Then we're not going to have the impact."

---

TDF Members: At press time, discount tickets were available for Key Change. Go here to browse all our theatre offers.

Follow Martha Wade Steketee at @msteketee. Follow TDF at @TDFNYC.

Photos by Keith Pattison. Top photo: Jessica Johnson (L) and Christina Berriman Dawson